Ladies and gentlemen, it is the second decade of the

third millennium and we are still kicking around the same 2-D interface

we got three decades ago. Sure, Apple debuted a few apps for

OSX 10.7 that have a couple more 3-D flourishes, and Microsoft has had that

Flip 3D for a while. But c’mon – 2011 is right around the corner. That’s

Twenty Eleven, folks. Where is our 3-D virtual reality? By now, we should be zipping around the

Metaverse on super-sonic motorbikes.

Granted, the capability of rendering complex 3-D environments has

been present for years. On the web, there are already several solutions:

Flash;

three.js in

<canvas>; and, eventually,

WebGL. Finally, we meagre front-end developers have our own three-dimensional jewel:

CSS 3-D transforms!

Rationale

Like a beautiful jewel, 3-D transforms can be dazzling, a true

spectacle to behold. But before we start tacking 3-D diamonds and rubies

to our compositions like

Liberace‘s tailor, we owe it to our users to ask how they can benefit from this awesome feature.

An entire application should not take advantage of 3-D transforms.

CSS

was built to style documents, not generate explorable environments. I

fail to find a benefit to completing a web form that can be accessed by

swivelling my viewport to the Sign-Up Room (although there have been

proposals to make the web just that). Nevertheless, there are plenty of

opportunities to use 3-D transforms

in between interactions with the interface, via transitions.

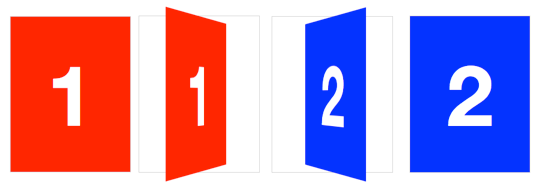

Take, for instance, the Weather App on the iPhone. The application

uses two views: a details view; and an options view. Switching between

these two views is done with a 3-D flip transition. This informs the

user that the interface has two – and only two – views, as they can

exist only on either side of the same plane.

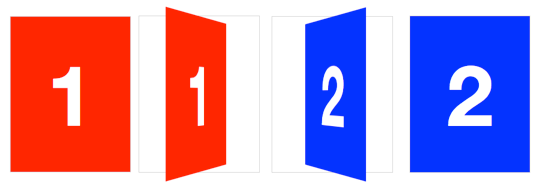

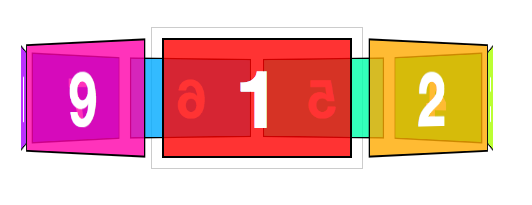

Flipping from details view to options view via a 3-D transition

Flipping from details view to options view via a 3-D transition

Also, consider slide shows. When you’re looking at the last slide,

what cues tip you off that advancing will restart the cycle at the first

slide? A better paradigm might be achieved with a 3-D transform,

placing the slides side-by-side in a circle (carousel) in

three-dimensional space; in that arrangement, the last slide obviously

comes before the first.

3-D transforms are more than just eye candy. We can also use them to solve dilemmas and make our applications more intuitive.

Current support

The

CSS 3D Transforms module

has been out in the wild for over a year now. Currently, only Safari

supports the specification – which includes Safari on Mac OS X and

Mobile Safari on iOS.

The support roadmap for other browsers varies. The Mozilla team has

taken some initial steps towards implementing the module.

Mike Taylor tells me that the Opera team is keeping a close eye on

CSS

transforms, and is waiting until the specification is fleshed out. And

our best friend Internet Explorer still needs to catch up to 2-D

transforms before we can talk about the 3-D variety.

To make matters more perplexing, Safari’s WebKit cousin Chrome

currently accepts 3-D transform declarations, but renders them in 2-D

space. Chrome team member

Paul Irish, says that 3-D transforms are on the horizon, perhaps in one of the next 8.0 releases.

This all adds up to a bit of a challenge for those of us excited by

3-D transforms. I’ll give it to you straight: missing the dimension of

depth can make degradation a bit ungraceful. Unless the transform is

relatively simple and holds up in non-3D-supporting browsers, you’ll

most likely have to design another solution. But what’s another hurdle

in a steeplechase? We web folk have had our mettle tested for years.

We’re prepared to devise multiple solutions.

Here’s the part of the article where I mention

Modernizr,

and you brush over it because you’ve read this part of an article

hundreds of times before. But seriously, it’s the best way to test for

CSS 3-D transform support. Use it.

Even with these difficulties mounting up, trying out 3-D transforms today is the right move. The

CSS 3-D transforms module was developed by the same team at Apple that produced the

CSS 2D Transforms and

Animation

modules. Both specifications have since been adopted by Mozilla and

Opera. Transforming in three-dimensions now will guarantee you’ll be

ahead of the game when the other browsers catch up.

The choice is yours. You can make excuses and pooh-pooh 3-D

transforms because they’re too hard and only snobby Apple fans will see

them today. Or, with a

tip of the fedora to Mr Andy Clarke, you can get hard-boiled and start designing with the best features out there right this instant.

So, I bid you,

in the words of the eternal Optimus Prime…

Transform and roll out.

Let’s get coding.

Perspective

To activate 3-D space, an element needs perspective. This can be applied in two ways: using the

transform property, with the perspective as a functional notation:

-webkit-transform: perspective(600);

or using the

perspective property:

-webkit-perspective: 600;

See example: Perspective 1.

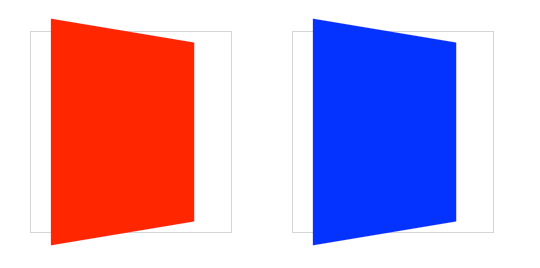

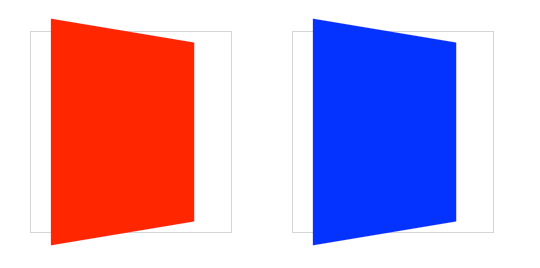

The red element on the left uses

The red element on the left uses transform: perspective() functional notation; the blue element on the right uses the perspective property

These two formats both trigger a 3-D space, but there is a

difference. The first, functional notation is convenient for directly

applying a 3-D transform on a single element (in

the previous example, I use it in conjunction with a

rotateY transform). But when used on multiple elements, the transformed elements don’t line up as expected. If you use the same

transform across elements with different positions, each element will have its own vanishing point. To remedy this, use the

perspective property on a parent element, so each child shares the same 3-D space.

See Example: Perspective 2.

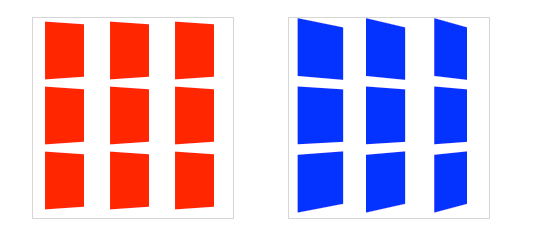

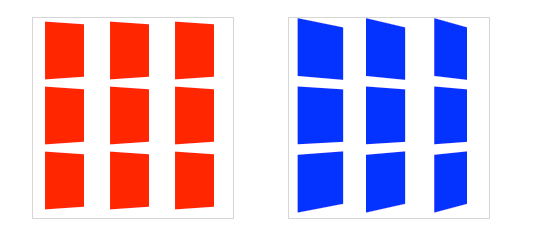

Each

red box on the left has its own vanishing point within the parent

container; the blue boxes on the right share the vanishing point of the

parent container

Each

red box on the left has its own vanishing point within the parent

container; the blue boxes on the right share the vanishing point of the

parent container

The value of

perspective determines the intensity of

the 3-D effect. Think of it as a distance from the viewer to the object.

The greater the value, the further the distance, so the less intense

the visual effect.

perspective: 2000; yields a subtle 3-D effect, as if we were viewing an object from far away.

perspective: 100; produces a tremendous 3-D effect, like a tiny insect viewing a massive object.

By default, the vanishing point for a 3-D space is positioned at its

centre. You can change the position of the vanishing point with

perspective-origin property.

-webkit-perspective-origin: 25% 75%;

See Example: Perspective 3.

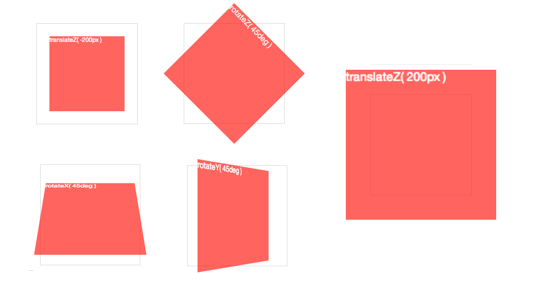

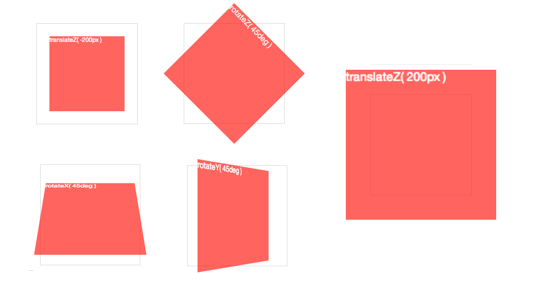

3-D transform functions

As a web designer, you’re probably well acquainted with working in

two dimensions, X and Y, positioning items horizontally and vertically.

With a 3-D space initialised with

perspective, we can now transform elements in all three glorious spatial dimensions, including the third Z dimension, depth.

3-D transforms use the same

transform property used for 2-D transforms. If you’re familiar with 2-D transforms, you’ll find the basic

3D transform functions fairly similar.

rotateX(angle)rotateY(angle)rotateZ(angle)translateZ(tz)scaleZ(sz)

Whereas

translateX() positions an element along the horizontal X-axis,

translateZ()

positions it along the Z-axis, which runs front to back in 3-D space.

Positive values position the element closer to the viewer, negative

values further away.

The

rotate functions rotate the element around the

corresponding axis. This is somewhat counter-intuitive at first, as you

might imagine that

rotateX will spin an object left to right. Instead, using

rotateX(45deg) rotates an element

around the horizontal X-axis, so the top of the element angles back and away, and the bottom gets closer to the viewer.

See Example: Transforms 1.

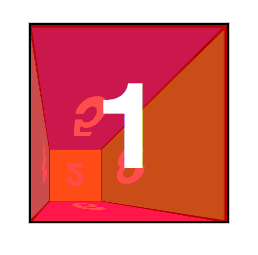

3-D

3-D rotate() and translate() functions around each axis

There are also several shorthand

transform functions that require values for all three dimensions:

translate3d(tx,ty,tz)scale3d(sx,sy,sz)rotate3d(rx,ry,rz,angle)

Pro-tip: These

foo3d() transform functions also have the benefit of triggering hardware acceleration in Safari. Dean Jackson,

CSS 3-D transform spec author and main WebKit dude, writes (to

Thomas Fuchs):

In essence, any transform that has a 3D operation as one of its

functions will trigger hardware compositing, even when the actual

transform is 2D, or not doing anything at all (such as translate3d(0,0,0)).

Note this is just current behaviour, and could change in the future

(which is why we don’t document or encourage it). But it is very helpful

in some situations and can significantly improve redraw performance.

For the sake of simplicity, my demos will use the basic transform functions, but if you’re writing production-ready

CSS for iOS or Safari-only,

make sure to use the foo3d() functions to get the best rendering performance.

Card flip

We now have all the tools to start making 3-D objects. Let’s get started with something simple: flipping a card.

Here’s the basic markup we’ll need:

<section class="container">

<div id="card">

<figure class="front">1</figure>

<figure class="back">2</figure>

</div>

</section>

The

.container will house the 3-D space. The

#card acts as a wrapper for the 3-D object. Each face of the card has a separate element:

.front; and

.back.

Even for such a simple object, I recommend using this same pattern for

any 3-D transform. Keeping the 3-D space element and the object

element(s) separate establishes a pattern that is simple to understand

and easier to style.

We’re ready for some 3-D stylin’. First, apply the necessary

perspective to the parent 3-D space, along with any size or positioning styles.

.container {

width: 200px;

height: 260px;

position: relative;

-webkit-perspective: 800;

}

Now the

#card element can be transformed in its

parent’s 3-D space. We’re combining absolute and relative positioning so

the 3-D object is removed from the flow of the document. We’ll also add

width: 100%; and

height: 100%;. This ensures the object’s

transform-origin will occur in the centre of

.container. More on

transform-origin later.

Let’s add a CSS3 transition so users can see the transform take effect.

#card {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

position: absolute;

-webkit-transform-style: preserve-3d;

-webkit-transition: -webkit-transform 1s;

}

The

.container’s

perspective only applies to direct descendant children, in this case

#card.

In order for subsequent children to inherit a parent’s perspective, and

live in the same 3-D space, the parent can pass along its perspective

with

transform-style: preserve-3d. Without 3-D

transform-style, the faces of the card would be flattened with its parents and the back face’s rotation would be nullified.

To position the faces in 3-D space, we’ll need to reset their positions in 2-D with

position: absolute. In order to hide the reverse sides of the faces when they are faced away from the viewer, we use

backface-visibility: hidden.

#card figure {

display: block;

position: absolute;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

-webkit-backface-visibility: hidden;

}

To flip the

.back face, we add a basic 3-D transform of

rotateY(180deg).

#card .front {

background: red;

}

#card .back {

background: blue;

-webkit-transform: rotateY(180deg);

}

With the faces in place, the

#card requires a corresponding style for when it is flipped.

#card.flipped {

-webkit-transform: rotateY(180deg);

}

Now we have a working 3-D object. To flip the card, we can toggle the

flipped class. When

.flipped, the

#card will rotate 180 degrees, thus exposing the

.back face.

See Example: Card 1.

Flipping a card in three dimensions

Flipping a card in three dimensions

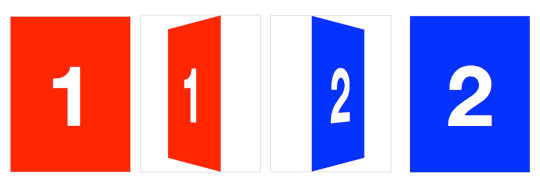

Slide-flip

Take another look at the Weather App 3-D transition. You’ll notice that it’s not quite the same effect as

our previous demo.

If you follow the right edge of the card, you’ll find that its corners

stay within the container. Instead of pivoting from the horizontal

centre, it pivots on that right edge. But the transition is not just a

rotation – the edge moves horizontally from right to left. We can

reproduce this transition just by modifying a couple of lines of

CSS from our original card flip demo.

The pivot point for the rotation occurs at the right side of the card. By default, the

transform-origin of an element is at its horizontal and vertical centre (

50% 50% or

center center). Let’s change it to the right side:

#card { -webkit-transform-origin: right center; }

That flip now needs some horizontal movement with

translateX. We’ll set the rotation to

-180deg so it flips right side out.

#card.flipped {

-webkit-transform: translateX(-100%) rotateY(-180deg);

}

See Example: Card 2.

Creating a slide-flip from the right edge of the card

Creating a slide-flip from the right edge of the card

Cube

Creating 3-D card objects is a good way to get started with 3-D

transforms. But once you’ve mastered them, you’ll be hungry to push it

further and create some true 3-D objects: prisms. We’ll start out by

making a cube.

The markup for the cube is similar to the card. This time, however, we need six child elements for all six faces of the cube:

<section class="container">

<div id="cube">

<figure class="front">1</figure>

<figure class="back">2</figure>

<figure class="right">3</figure>

<figure class="left">4</figure>

<figure class="top">5</figure>

<figure class="bottom">6</figure>

</div>

</section>

Basic position and size styles set the six faces on top of one another in the container.

.container {

width: 200px;

height: 200px;

position: relative;

-webkit-perspective: 1000;

}

#cube {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

position: absolute;

-webkit-transform-style: preserve-3d;

}

#cube figure {

width: 196px;

height: 196px;

display: block;

position: absolute;

border: 2px solid black;

}

With the card, we only had to rotate its back face. The cube,

however, requires that five of the six faces to be rotated. Faces 1 and 2

will be the front and back. Faces 3 and 4 will be the sides. Faces 5

and 6 will be the top and bottom.

#cube .front { -webkit-transform: rotateY(0deg); }

#cube .back { -webkit-transform: rotateX(180deg); }

#cube .right { -webkit-transform: rotateY(90deg); }

#cube .left { -webkit-transform: rotateY(-90deg); }

#cube .top { -webkit-transform: rotateX(90deg); }

#cube .bottom { -webkit-transform: rotateX(-90deg); }

We could remove the first

#cube .front style declaration, as this transform has no effect, but let’s leave it in to keep our code consistent.

Now each face is rotated, and only the front face is visible. The

four side faces are all perpendicular to the viewer, so they appear

invisible. To push them out to their appropriate sides, they need to be

translated out from the centre of their positions. Each side of the cube

is 200 pixels wide. From the cube’s centre they’ll need to be

translated out half that distance,

100px.

#cube .front { -webkit-transform: rotateY(0deg) translateZ(100px); }

#cube .back { -webkit-transform: rotateX(180deg) translateZ(100px); }

#cube .right { -webkit-transform: rotateY(90deg) translateZ(100px); }

#cube .left { -webkit-transform: rotateY(-90deg) translateZ(100px); }

#cube .top { -webkit-transform: rotateX(90deg) translateZ(100px); }

#cube .bottom { -webkit-transform: rotateX(-90deg) translateZ(100px); }

Note here that the

translateZ function comes

after the

rotate.

The order of transform functions is important. Take a moment and soak

this up. Each face is first rotated towards its position, then

translated outward in a separate vector.

We have a working cube, but we’re not done yet.

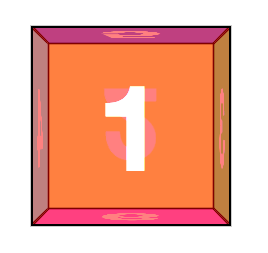

Returning to the Z-axis origin

For the sake of our users, our 3-D transforms should not distort the

interface when the active panel is at its resting position. But once we

start pushing elements off their Z-axis origin, distortion is

inevitable.

In order to keep 3-D transforms snappy, Safari composites the

element, then applies the transform. Consequently, anti-aliasing on text

will remain whatever it was

before the transform was applied. When transformed forward in 3-D space, significant pixelation can occur.

See Example: Transforms 2.

Looking back at the

Perspective 3 demo, note that no matter how small the perspective value is, or wherever the

transform-origin may be, the panel number 1 always returns to its original position, as if all those funky 3-D transforms didn’t even matter.

To resolve the distortion and restore pixel perfection to our

#cube, we can push the 3-D object back, so that the front face will be positioned back to the Z-axis origin.

#cube { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px); }

See Example: Cube 1.

Restoring the front face to the original position on the Z-axis

Restoring the front face to the original position on the Z-axis

Rotating the cube

To expose any face of the cube, we’ll need a style that rotates the

cube to expose any face. The transform values are the opposite of those

for the corresponding face. We toggle the necessary class on the

#box to apply the appropriate transform.

#cube.show-front { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateY(0deg); }

#cube.show-back { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateX(-180deg); }

#cube.show-right { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateY(-90deg); }

#cube.show-left { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateY(90deg); }

#cube.show-top { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateX(-90deg); }

#cube.show-bottom { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateX(90deg); }

Notice how the order of the transform functions has reversed. First, we push the object back with

translateZ, then we rotate it.

Finishing up, we can add a

transition to animate the rotation between states.

#cube { -webkit-transition: -webkit-transform 1s; }

See Example: Cube 2.

Rotating the cube with a CSS

Rotating the cube with a CSS transition

Rectangular prism

Cubes are easy enough to generate, as we only have to worry about

one measurement. But how would we handle a non-regular rectangular

prism? Let’s try to make one that’s 300 pixels wide, 200 pixels high,

and 100 pixels deep.

The markup remains the same as the

#cube, but we’ll switch the

cube id for

#box. The container styles remain mostly the same:

.container {

width: 300px;

height: 200px;

position: relative;

-webkit-perspective: 1000;

}

#box {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

position: absolute;

-webkit-transform-style: preserve-3d;

}

Now to position the faces. Each set of faces will need their own

sizes. The smaller faces (left, right, top and bottom) need to be

positioned in the centre of the container, where they can be easily

rotated and then shifted outward. The thinner left and right faces get

positioned

left: 100px ((300 − 100) ÷ 2), The stouter top and bottom faces get positioned

top: 50px ((200 − 100) ÷ 2).

#box figure {

display: block;

position: absolute;

border: 2px solid black;

}

#box .front,

#box .back {

width: 296px;

height: 196px;

}

#box .right,

#box .left {

width: 96px;

height: 196px;

left: 100px;

}

#box .top,

#box .bottom {

width: 296px;

height: 96px;

top: 50px;

}

The rotate values can all remain the same as the cube example, but

for this rectangular prism, the translate values do differ. The front

and back faces are each shifted out 50 pixels since the

#box

is 100 pixels deep. The translate value for the left and right faces is

150 pixels for their 300 pixels width. Top and bottom panels take 100

pixels for their 200 pixels height:

#box .front { -webkit-transform: rotateY(0deg) translateZ(50px); }

#box .back { -webkit-transform: rotateX(180deg) translateZ(50px); }

#box .right { -webkit-transform: rotateY(90deg) translateZ(150px); }

#box .left { -webkit-transform: rotateY(-90deg) translateZ(150px); }

#box .top { -webkit-transform: rotateX(90deg) translateZ(100px); }

#box .bottom { -webkit-transform: rotateX(-90deg) translateZ(100px); }

See Example: Box 1.

Just like the cube example, to expose a face, the

#box needs to have a style to reverse that face’s transform. Both the

translateZ and

rotate values are the opposites of the corresponding face.

#box.show-front { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-50px) rotateY(0deg); }

#box.show-back { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-50px) rotateX(-180deg); }

#box.show-right { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-150px) rotateY(-90deg); }

#box.show-left { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-150px) rotateY(90deg); }

#box.show-top { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateX(-90deg); }

#box.show-bottom { -webkit-transform: translateZ(-100px) rotateX(90deg); }

See Example: Box 2.

Rotating the rectangular box with a CSS

Rotating the rectangular box with a CSS transition

Carousel

Front-end developers have a myriad of choices when it comes to

content carousels. Now that we have 3-D capabilities in our browsers,

why not take a shot at creating an actual 3-D carousel?

The markup for this demo takes the same form as the box, cube and

card. Let’s make it interesting and have a carousel with nine panels.

<div class="container">

<div id="carousel">

<figure>1</figure>

<figure>2</figure>

<figure>3</figure>

<figure>4</figure>

<figure>5</figure>

<figure>6</figure>

<figure>7</figure>

<figure>8</figure>

<figure>9</figure>

</div>

</div>

Now, apply basic layout styles. Let’s give each panel of the

#carousel 20 pixel gaps between one another, done here with

left: 10px; and

top: 10px;. The effective width of each panel is 210 pixels.

.container {

width: 210px;

height: 140px;

position: relative;

-webkit-perspective: 1000;

}

#carousel {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

position: absolute;

-webkit-transform-style: preserve-3d;

}

#carousel figure {

display: block;

position: absolute;

width: 186px;

height: 116px;

left: 10px;

top: 10px;

border: 2px solid black;

}

Next up: rotating the faces. This

#carousel has nine

panels. If each panel gets an equal distribution on the carousel, each

panel would be rotated forty degrees from its neighbour (360 ÷ 9).

#carousel figure:nth-child(1) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(0deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(2) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(40deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(3) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(80deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(4) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(120deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(5) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(160deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(6) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(200deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(7) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(240deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(8) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(280deg); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(9) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(320deg); }

Now, the outward shift. Back when we were creating the cube and box, the

translate

value was simple to calculate, as it was equal to one half the width,

height or depth of the object. With this carousel, there is no size we

can automatically use as a reference. We’ll have to calculate the

distance of the shift by other means.

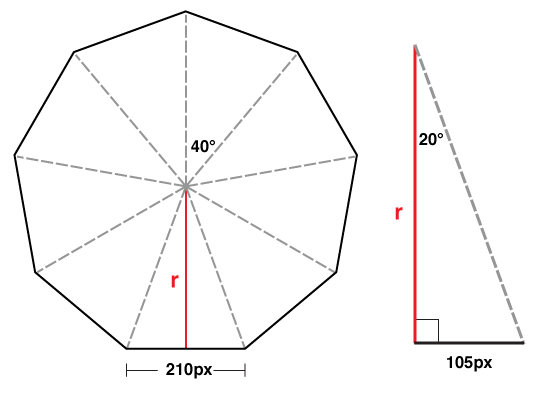

Drawing a diagram of the carousel, we can see that we know only two

things: the width of each panel is 210 pixels; and the each panel is

rotated forty degrees from the next. If we split one of these segments

down its centre, we get a right-angled triangle, perfect for some

trigonometry.

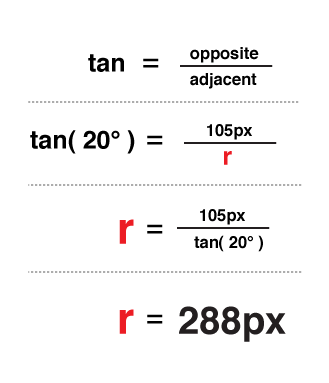

We can determine the length of

r in this diagram with a basic tangent equation:

There you have it: the panels need to be translated 288 pixels in 3-D space.

#carousel figure:nth-child(1) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(0deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(2) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(40deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(3) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(80deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(4) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(120deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(5) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(160deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(6) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(200deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(7) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(240deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(8) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(280deg) translateZ(288px); }

#carousel figure:nth-child(9) { -webkit-transform: rotateY(320deg) translateZ(288px); }

If we decide to change the width of the panel or the number of

panels, we only need to plug in those two variables into our equation to

get the appropriate

translateZ value. In JavaScript terms, that equation would be:

var tz = Math.round( ( panelSize / 2 ) /

Math.tan( ( ( Math.PI * 2 ) / numberOfPanels ) / 2 ) );

// or simplified to

var tz = Math.round( ( panelSize / 2 ) /

Math.tan( Math.PI / numberOfPanels ) );

Just like our previous 3-D objects, to show any one panel we need

only apply the reverse transform on the carousel. Here’s the style to

show the fifth panel:

-webkit-transform: translateZ(-288px) rotateY(-160deg);

See Example: Carousel 1.

By now, you probably have two thoughts:

- Rewriting transform styles for each panel looks tedious.

- Why bother doing high school maths? Aren’t robots supposed to be doing all this work for us?

And you’re absolutely right. The repetitive nature of 3-D objects

lends itself to scripting. We can offload all the monotonous transform

styles to our dynamic script, which, if done correctly, will be more

flexible than the hard-coded version.

See Example: Carousel 2.

Conclusion

3-D transforms change the way we think about the blank canvas of web

design. Better yet, they change the canvas itself, trading in the flat

surface for voluminous depth.

My hope is that you took at least one peak at a demo and were intrigued. We web designers, who have rejoiced for

border-radius,

box-shadow

and background gradients, now have an incredible tool at our disposal

in 3-D transforms. They deserve just the same enthusiasm, research and

experimentation we have seen on other CSS3 features. Now is the perfect

time to take the plunge and start thinking about how to use three

dimensions to elevate our craft. I’m breathless waiting for what’s to

come.

See you on the flip side.

Close Me!

Close Me!